The Unifying Element

A look into Jeff Mills’s Purpose Maker Imagery

Listen as you read for the best possible experience

Even though Jeff Mills is often associated with modern-day experimentation and his early ‘90s industrial sound, his range as an artist is nearly limitless. After resetting the techno landscape with the Waveform Transmission series, Mills released AX-11 in 1995. Titled The Purpose Maker, the record was a marked departure from the ruthless futurism of earlier Axis releases. There was some basis in Mills’s previous work, namely the locked grooves of Cycle 30, but the sound was shrouded in mystery. It’s a driving concoction of organic percussion and cybernetic programming that startles the ears, bypassing logical faculties and entrenching itself somewhere in the nervous system.

Purpose Maker would eventually develop into a standalone label housing Mills’s most functional productions, and it played a major role in launching the tribal techno craze of the late ‘90s, serving as a leading reference point for producers like Ben Sims and Samuel L. Session. While some records from this period quickly revealed themselves to be overly simplistic and uninspired, Mills’s tracks still slice through the crowd like a flaming sword.

Java label and Mary Wigman’s Dancing Hands (1928)

I first got the idea for this article when listening to Java, the first (and, in my opinion, best) Purpose Maker record. After playing it 3 or 4 times, I took a closer look at the artwork. A serpentine collage of hands contorting and stabbing at each other, vaguely reminiscent of Shiva, the destructive Hindu lord of the dance. The image is an ideal match for the frenzied sound: it conveys energy and gestures toward the unknown. Upon further research, Discogs handed me a lead. The hands belong to Mary Wigman, a dancer in the 1920s who garnered significant acclaim for her frantic, flowing performances that rejected highly-structured classical notions of movement. Wigman was photographed by Charlotte Rudolph, who had an uncanny ability to capture motion in a still image.

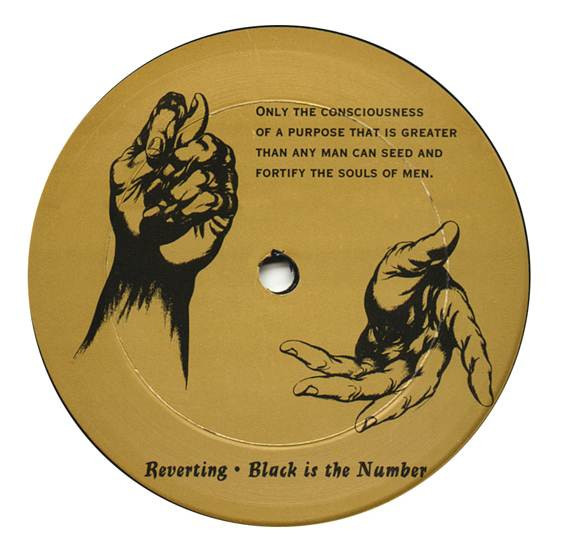

For at least a week of further research, I assumed that Mills’s other Purpose Maker releases also used Charlotte Rudolph photographs on their label artwork. Hours of reverse image searching and squinting at Google results led to dead end after dead end. Eventually, I gave up and conceded that the narrative was not going to be as satisfying as I wanted it to be. I thought this article was going to be about Rudolph and Mills’s artistic alignment, but as I dug, I started to realize it was about Jeff Mills’s fixation with hands.

They’re inescapable: In the Purpose Maker logo and on the artwork of almost every release, highlighted in these force field-like circles. After a bit of deliberation, the connection started to take shape.

Aside from the face, the hands are the most expressive part of our bodies. They can assume a broad range of positions, displaying tension, euphoria, restlessness, or remorse. However, their secondary status to the face means that they simultaneously convey and encode our identities. Fingerprints are unique, but we can’t decipher them with the naked eye, and hands are rarely viewed as an identifying characteristic. Hands are also inherently functional: they are our primary means of building, and they are the reason that humans were able to create tools and evolve at an exponential pace.

Photographs of Jeff Mills’s hands taken by Riva Sayegh for a 1998 exhibition organized by Tresor

A DJ set has certain traits that are rarely seen in other types of performance. A rockstar travels the world playing a nearly-identical set list and their face is plastered on everything from merchandise to advertising. Walk into a proper club, and you won’t be able to see the DJ past the molecular structure of sweating bodies and artificial fog. The music is also anonymized to the point where you can hardly tell when one track moves into the next, let alone name the producer or song title.

And perhaps most importantly, the person up front is at the mercy of the crowd. If a DJ can’t read the room, they’re in the wrong line of work. A continuous sequence of sound adjustment must be executed in a way that is both reactive and predictive, resulting in a performance that is closer to a dialogue than a staged production.

Java is a prime example of how Jeff Mills approached his Purpose Maker recordings. The track uses a vocal sample from Electrik Funk’s 1982 disco hit “I Sing The Funk Electric” and morphs it into a feverish prehistoric chant. Pitched up and repeated over the course of 4 minutes, the words quickly become unrecognizable. Mills also plays with the sample’s volume to create subtle build-ups within the composition: the percussive base provides a constant groove while the vocal slithers in and out of the mix, sometimes disappearing entirely. To complete the track, Mills paired the sample with a monstrous open hi-hat and a cluster of 3 kicks on the second and fourth beats to augment the 4/4 pattern, resulting in one of the most lethal dancefloor weapons of the 1990s.

A workmanlike view of records as tools lies at the center of each Purpose Maker release. These tracks are engineered for physicality, and they follow a barebones formula of sampled funk loops, tribal drums, and a powerful 4/4 kick. Their simplicity encourages audacious blending, ensuring that the DJ’s technical skill and creativity is at the forefront of a performance.

Mills has stated that the early Purpose Maker records were produced strictly for his sets with no intention of a wider release, and this checks out upon first listen: they are tailor-made for his extremely active mixing style and they reflect his personal vision of a DJ’s role. In a perfect world, identity becomes irrelevant once the music begins, for both the crowd and the DJ. If energy is properly channeled, the crowd is driven into an animistic hysteria of cheers and yelps, flailing limbs, and physical exhaustion, creating a genuine release of tension by tearing down the inhibitions of daily life.

An effective tool offers a straightforward solution to basic human needs. Footwear enables movement, telephones enable communication, and instruments enable expression. However, a fervent desire for extra features has emerged in recent years, and innovation has gotten to the point where minor improvements often negate themselves by adding yet another layer of complexity. In such a landscape, a technical step backwards can represent a conceptual step forwards. Jeff Mills’s Purpose Maker productions shift the transformative responsibility away from the producer and towards the DJ, and they prove that the basic structure of rhythm-based music remains effective, regardless of audience or time period. Ancient percussion, 1980s funk, and digital production techniques coalesce like a metal alloy: impurities are boiled down into synergistic strength.

As a ubiquitous symbol of expression and connection, hands are an ideal calling card for the Purpose Maker universe. They represent an intimate involvement between all those who contribute to the ritual of a dance, and they champion a form of communication that transcends language. The back label of AX-11 includes a quote from American journalist Walter Lippman. It reads as follows: